Art. 17 GDPR Right to erasure (‘right to be forgotten’)

Google your younger self – your full name and/or the first email address that you ever created and see what you find. It may be funny to come across a review or comment that you had publicly posted for a restaurant or a salon 10-12 years back. However, if you are a professional, an entrepreneur or trying to set yourself up as a business owner, this may also affect your brand image negatively.

Something similar happened to a Dutch doctor when her registration on the register of healthcare professionals was initially suspended by a disciplinary panel because of her postoperative care of a patient. After an appeal, this was changed to a conditional suspension under which she could continue to practice.

However, due to a misleading media report, every time someone entered her full name in Google’s search engine, (almost) immediately the mention of her name appeared on the ‘blacklist of doctors’,

The Ruling

When the surgeon tried to reason with Google and the Dutch data protection office, Autoriteit Persoonsgegevens, about removing the erroneous link, they rejected it citing that since, she was still on probation, the information remained relevant.

However, in what is said to be the first “Right to be Forgotten” ruling, involving medical negligence by a doctor, the district court of Amsterdam subsequently ruled that the surgeon had “an interest in not indicating that every time someone enters their full name in Google’s search engine, (almost) immediately the mention of her name appears on the ‘blacklist of doctors’ and this importance adds more weight than the public’s interest in finding this information in this way”.

What is the right to be forgotten?

The right to be forgotten appears in Recitals 65 and 66, and in Article 17 of the GDPR. It states: “The data subject shall have the right to obtain from the controller the erasure of personal data concerning him or her without undue delay and the controller shall have the obligation to erase personal data without undue delay” if one of a number of conditions applies. “Undue delay” is considered to be about a month. You must also take reasonable steps to verify the person requesting erasure is actually the data subject.

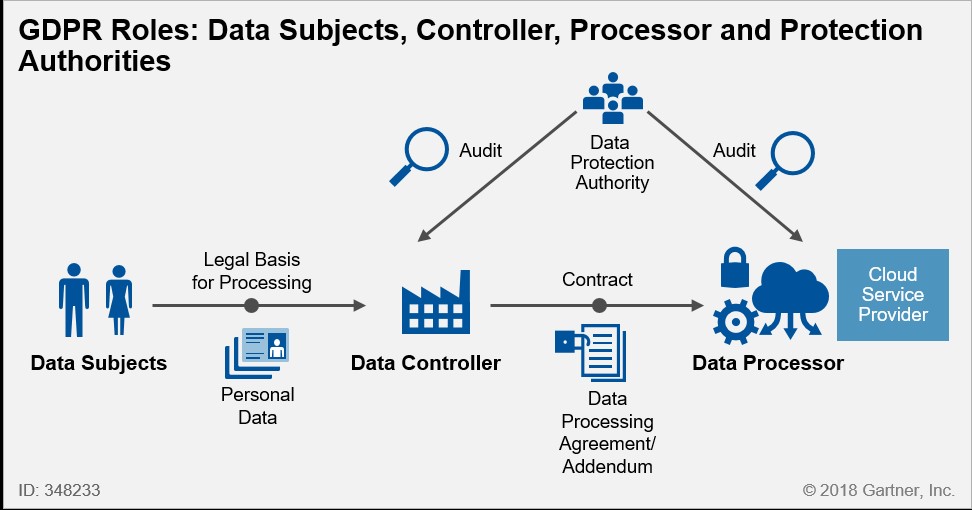

GDPR defines the following roles for the purpose of understanding this article:

Data Subject, Data Controller and Data Processor

The right to be forgotten dovetails with people’s right to access their personal information Article 15. The right to control one’s data is meaningless if people cannot take action when they no longer consent to processing, when there are significant errors within the data or if they believe information is being stored unnecessarily. In these cases, an individual can request that the data be erased. But this is not completely certain. If it were the critics who argue that the right to be forgotten amounts to nothing more than a rewriting of history would be correct. Thus, the GDPR walks a fine line on data erasure.

When does the right to be forgotten apply?

In Article 17, the GDPR outlines the specific circumstances under which the right to be forgotten applies. An individual has the right to have their personal data erased if:

• The personal data is no longer necessary for the purpose an organization originally collected or processed it.

• An organization is relying on an individual’s consent as the lawful basis for processing the data and that individual withdraws their consent.

• An organization is relying on legitimate interests as its justification for processing an individual’s data, the individual objects to this processing, and there is no overriding legitimate interest for the organization to continue with the processing.

• An organization is processing personal data for direct marketing purposes and the individual objects to this processing.

• An organization processed an individual’s personal data unlawfully.

• An organization must erase personal data in order to comply with a legal ruling or obligation.

• An organization has processed a child’s personal data to offer their services.

However, an organization’s right to process someone’s data might override their right to be forgotten. Here are the reasons cited in the GDPR that supersede the right to erasure:

• The data is being used to exercise the right of freedom of expression and information.

• The data is being used to comply with a legal ruling or obligation.

• The data is being used to perform a task that is being carried out in the public interest or when exercising an organization’s official authority.

• The data being processed is necessary for public health purposes and serves in the public interest.

• The data being processed is necessary to perform preventative or occupational medicine. This only applies when the data is being processed by a health professional who is subject to a legal obligation of professional secrecy.

• The data represents important information that serves the public interest, scientific research, historical research or statistical purposes and where erasure of the data would likely impair or halt progress towards the achievement that was the goal of the processing.

• The data is being used for the establishment of a legal defense or in the exercise of other legal claims.

Furthermore, an organization can request a “reasonable fee” or deny a request to erase personal data if the organization can justify that the request was unfounded or excessive.

As you can see, there are many variables at play and each request will have to be evaluated individually. Add to that the technical burden of keeping track of all the places an individual’s personal data is stored or processed, and it is easy to see why the GDPR’s new privacy rights can be a significant compliance burden for some organizations.

About the Authors

Settled in The Hague, Punita is an electronics and telecom engineer by education. She has run Information Security programs and Audits for French/Indian multinational firms across the Middle east, Europe, India and Malaysia.

Jasmeeta is a marketing professional and works for an IT firm. She likes to bake on the weekends. Clearly sleep-deprived, she also lives in The Hague, for now. Plays pranks, most of the time. Travels, when she gets the calling.

References-https://gdpr.eu/

https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2019/jan/21/dutch-surgeon-wins-landmark-right-to-be-forgotten-case-google